Spinning Samples.

Last week, the Spinning Interest Group at Local Cloth worked with two samples brought by Judi Jetson, the leader of this interest group. The first was some washed Blue Ridge Mountain Blend (wool, mohair, and alpaca). We have explored an earlier version last year during one of our interest group meetings (blog link here; Blue Ridge Mountains Blend #1, 30% Montadale, 25% Shetland, 25% Alpaca, 20% Mohair). The second sample we explored this month was some washed Polled Dorset.

The Blue Ridge Mountain Blend, made from fibers grown by farmers in our Blue Ridge Mountain Fibershed, will be woven into blankets as a part of the Blue Ridge Blanket Project. More on that later; a new link in the Local Cloth webpage is nearing completion and I plan to periodically blog on the progress of this newly funded initiative by Local Cloth.

Our interest group participants enjoyed spinning this fiber because it was very easy to spin, soft to the touch and fuzzy, and had a lovely sheen creating an overall beautiful result. I spun singles from which Judi made two-ply yarn. Below is a photo of the resulting yarn. I will test it knitted up and save a portion for weaving by others.

Blue Ridge Mountain Blend. Z-spun singles were spun into 2-ply using the single ball, two end method.

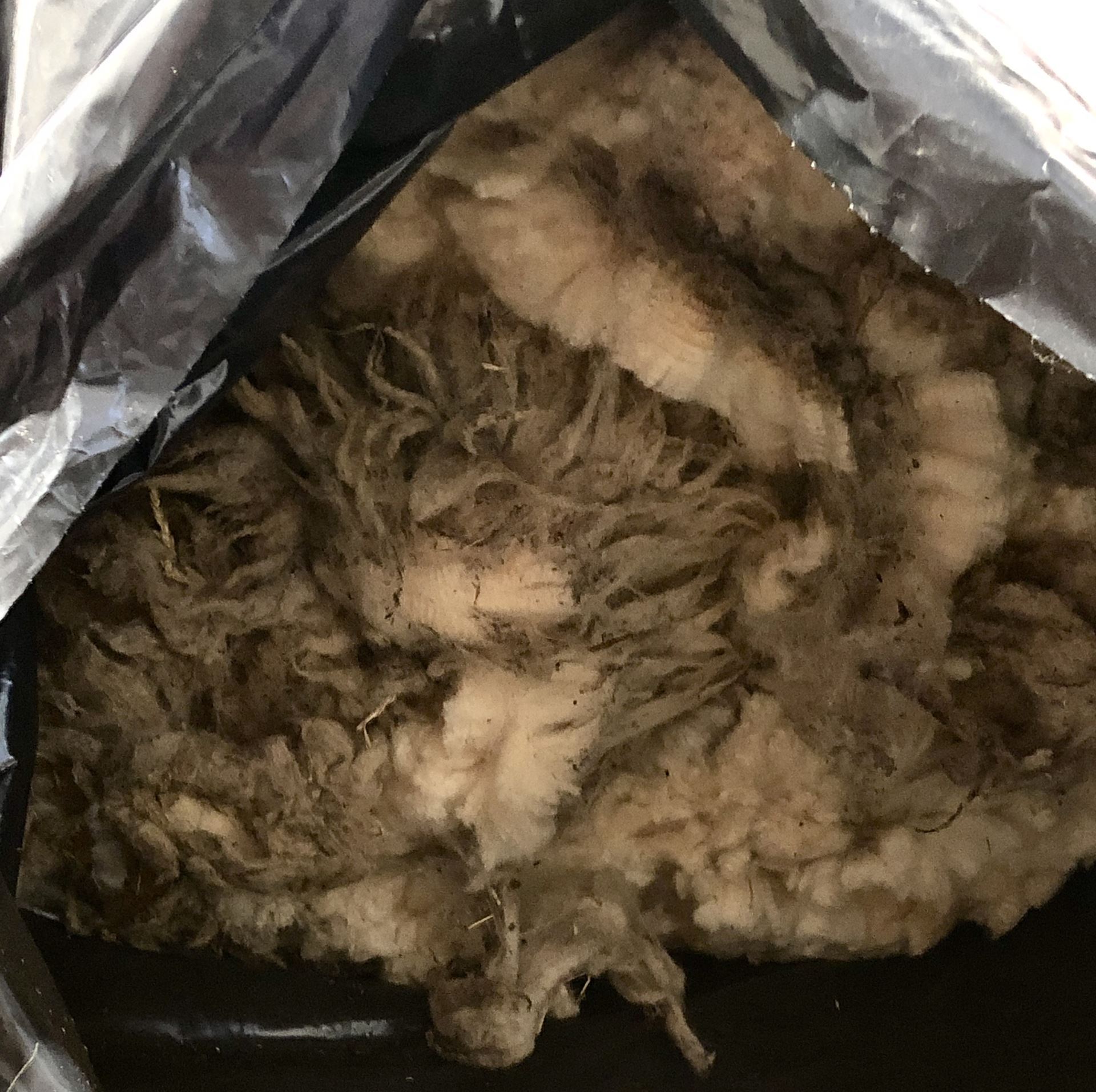

The second sample the Spinning Interest Group explored was a small amount of hand washed Polled Dorset fleece. We found that this portion of the fleece was sensitive to the method of washing because many noils were generated during the washing process.

An article by Kate Larson, 2018, in Spin Off Magazine describes differences between neps and noils with illustrations and ascribes them primarily to processing errors, particularly when washing very sensitive fleeces. Fibers contained within raw fleeces can break and tangle for a number of reasons including disease. Some fiber folk use the terms neps and noils interchangeably.

Never-the-less, during our session we tried combing, carding, and drum carding this fiber. Everyone gave up on it finding it too hard to spin and many hated the noils that clung tightly to the fiber. We all agreed that it should be processed professionally. I, however, driven by a stubborn streak and beingmore tolerant of noils, persisted with some hand carded fiber and got the results shown below. I don’t mind the fluffy bits that stick to the wool as I spin!

The above two photos show the Polled Dorset sample formed by spinning z-singles and then chain plying. The yarn was knit using #8 knitting needles.

Skirting Polled Dorset fleeces.

Anthony Cole was the origin of the Polled Dorset fleeces. He is a sheep shearer and 5th generation farmer living in Leicester, NC who after shearing Polled Dorset sheep didn’t want to keep the fleeces. After contacting Judi Jetson, he donated a 700 lb contractor bag filled with fleeces to Local Cloth. It still sits at the spot he deposited it because no one can move it!

Following the decision of our spinning group and others to send the fiber to a mill for processing, a skirting event was organized for once per week over several weeks. Volunteers will complete skirting the fleece to save on cost before bringing to a mill for processing.

Joining Judi and me at the first session was Josephine Brewer, Natalie Pollard, and her daugher Rosa Lee. Later Elizabeth joined me to finish and clean up. Elizabeth Strub of Hobby Knob Farm is a local fiber farmer and knows more about skirting a fleece.

So my first experience of skirting taught me it is an experience in lanolin. Lovely stuff in my opinion. First it feels dampish on your hands and then dries a bit later. Great for cracks in your fingers in the winter! Lanolin is also called grease. And, when spinning fiber that contains some, it is called spinning in the grease.

On the freshly sheared fleece, lanolin is mixed with dust, dirt, and sweat from the sheep. Throw in some bits of hay and some wood chips and you have a dirty fleece. It depends greatly on the type of surface that sheep encounter as to how much and what kind of dirt is retained in the wool. The neck, maybe the legs, the stomach, and the sheep’s bottom are especially dirty and bits of fleece there might be culled during skirting as too dirty or short.

Thus, skirting a fleece has nothing to do with a skirt that you wear. This is the first observation of the complete novice. It also is not exclusively an experience in picking out bits of dirt by hand. One must remove as much debris as possible, short cuts, weak or disease-affected fibers, and any fibers that are too short to use. We tried for at least 3” long when stretched out.

Samples of bits of fleece from various locations and with varying qualities of fiber and dirt content.

This section of the fleece is a keeper! Note the lovely crimp. The micron count was about 25 micrometers. The yellow is probably sheep sweat.

Although we shook the fleece to remove loose dirt and debris, the top of the fleece (tips of the fibers) was facing down and the clean cut side up. We flipped it over so that the dirty side was facing up and shook it and found that the short cuts adhering to the cut side fell out. There weren’t many. Short cuts form when the shearer backs up the shears and cuts slightly closer to the sheep’s skin. This results in the presence of short bits of fiber; these are too short to be processed and spun and so must be removed.

This coming week, more skirting.